James B. Stockdale: Stoic Warrior, POW Leader, Moral Beacon

On Navy Day, we honor those who fought for freedom in obvious ways—on battlefields, in storms of gunfire. James Bond Stockdale did those things, but his life also shows how much of the fight is internal: resisting cruelty, remaining human under dehumanizing conditions, holding to moral purpose when everything pushes you toward bitterness.

Early Life, Education, and Philosophic Groundwork

Stockdale was born on December 23, 1923, in Abingdon, Illinois. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy after a brief period at Monmouth College. An often-overlooked aspect: he later pursued graduate work in international relations and then shifted toward philosophy, especially Stoicism, studying thinkers like Epictetus. That philosophical grounding didn’t make his life easier, but it gave him tools to face torture, isolation, and uncertainty.

Combat, Capture, Torture: The Hardest Tests

In Vietnam, as commander of Carrier Air Wing Sixteen aboard the USS Oriskany, Stockdale flew in heavy combat. On September 9, 1965, his A-4 Skyhawk was shot down over North Vietnam. He was captured, badly injured, and would spend over seven years in captivity, including more than four years in solitary confinement.

During those years, he was tortured multiple times (at least 15 documented incidents), chained in leg irons, denied medical care, and forced to endure extreme deprivation. He was also one of the few POW leaders who resisted propaganda efforts: for example, when captors wanted to use him for a propaganda parade, he deliberately disfigured his face so they couldn’t.

He didn’t simply survive physically; he took on the role of organizing resistance among fellow prisoners. Furthermore, he taught and enforced the U.S. Code of Conduct among POWs, instigated—and taught—a “tap code” system, so prisoners could communicate covertly. Those acts of leadership saved lives, morale, and sanity.

Stockdale Paradox: Confront Reality, Retain Faith

One of Stockdale’s enduring legacies is what Jim Collins called the Stockdale Paradox. It’s the idea that in the worst circumstances, you must confront the brutal facts of your current reality while maintaining faith that you will prevail in the end. Optimism alone doesn’t cut it—naïve hope of release by next holiday can kill morale when those dates pass without fulfillment.

Stockdale observed that many POWs who were optimists (“We’ll be out by Christmas,” etc.) would eventually break under the weight of repeated disappointment. Those who survived longest balanced realism (this is horrible, this is what’s happening) with unshakable belief in ultimate justice and survival.

Post-Captivity: Ethics, Teaching, Public Life

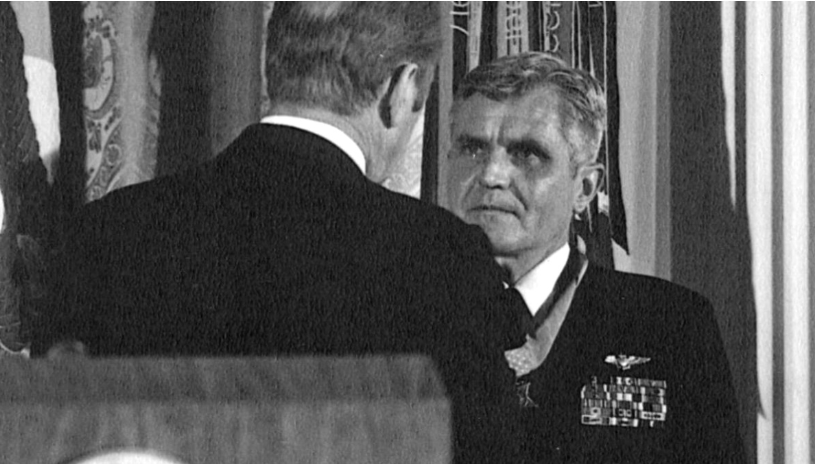

After his release in 1973, Stockdale didn’t slip into obscurity. He was awarded the Medal of Honor in 1976 for his leadership and conduct under torture. He later became President of the Naval War College (1977-1979), helping to shape future naval leaders. Furthermore, he also briefly served as President of The Citadel.

Not only that, but he published several books and essays reflecting on his experience—A Vietnam Experience: Ten Years of Reflection, Thoughts of a Philosophical Fighter Pilot, and In Love and War (co-authored with his wife Sybil). His post-war work wasn’t just memoir; he taught ethics—especially moral obligation—and led by example. Thousands of students at the Naval War College still take his “Foundations of Moral Obligation” coursework.

The Family & Moral Support: Sybil Stockdale’s Role

Stockdale’s courage in captivity mattered, but so did what happened at home. His wife, Sybil Stockdale, became a powerful advocate for POW/MIA families. She helped found the National League of POW/MIA Families and worked to get press and political attention on the treatment of POWs. Her correspondence with him (some letters coded) helped sustain morale and also helped communicate the outside world to prisoners.

Even more human: his children carried grief through those years. One story: while their dad was missing, the family refrained from buying new clothes; at dinner, sometimes they served just a small bowl of rice to remember his suffering and absence. These gestures show that service warps more than the battlefield—it warps families, norms, and childhood. Yet they also show that love, ritual, and memory are powerful tools of survival.

Lesser-Known Honors, Traits & Contributions

- Stockdale is the only U.S. Navy three-star officer to wear both aviator wings and the Medal of Honor.

- The Navy created the Vice Admiral James B. Stockdale Award for Inspirational Leadership in 1980, given annually to commanding officers (Atlantic & Pacific Fleets), recognizing leadership qualities Stockdale identified in his writings.

- Physical resilience: while captive, beyond torture, he was in leg irons for long periods, with broken legs, and a lack of medical care. Yet he established daily routines (exercise even in irons, prayer/meditation, mental discipline) to preserve not only body but mind.

Lessons for Navy Day & for Our Time

Stockdale’s life suggests several lessons, especially relevant in times of moral challenge, crisis, or when freedom seems under threat.

- Reality must be faced, however brutal

Denial or false hope can kill morale. Recognizing danger, suffering, and injustice is essential. That doesn’t mean losing hope—but without full awareness, you lose direction. - Moral purpose and personal responsibility sustain through suffering

For Stockdale, philosophy wasn’t academic—it was life or death. The internal compass mattered. Having a sense of what is right—by action, by leadership, by keeping commitments—gives meaning, even in captivity. - Leadership includes caring for the unseen wounds

Physical wounds heal more slowly or faster, but moral, psychological, and family wounds last. Stockdale’s care for his squad, his enforcement of codes, his teaching, and his support of families show leadership beyond orders. - Sacrifice continues after conflict

He didn’t vanish after being released. He taught, wrote, debated, and even ran for public office (1992, as Ross Perot’s VP choice), though political life was uncomfortable for him. He tried to bridge moral experience with public policy. - Legacy is built on example, not myth

The stories around Stockdale are powerful because they don’t sanitize. They allow pain, doubt, horror. Remembering him fully—bravery and suffering—gives us human role models, not superheroes.

Honoring Stockdale on Navy Day

On Navy Day, when we say “thank you” to veterans, we should remember not only those who fought physically but those who fought ethically, internally, those who held out when hope dimmed, those whose leadership wasn’t flashy but essential.

James Stockdale’s life reminds us that freedom isn’t only preserved by winning wars—it’s preserved by discipline, morality, truth, endurance, and human dignity. If we teach history that omits the cost, we risk losing the meaning of sacrifice. If we only celebrate triumph, we forget how fragile victory is when the price is overlooked.

Let us honor Stockdale by:

- Giving space for the full stories—of pain, doubt, resistance, pride.

- Supporting veterans’ mental health, families left behind, and moral burdens carried long after wars end.

- Elevating values like responsibility, integrity, leadership grounded in service, not ambition.

- Recognizing that individuals like Stockdale do more than survive—they show how a man can turn suffering into purpose.